|

A few years ago two pictures from Trinity College were put on display at the Fitzwilliam Museum. The college has a collection of about 240 paintings, most of which are portraits of past alumni, masters and fellows but these two paintings reflected the college’s royal connections. The first was a large portrait of King Henry VIII, the college’s founder and patron. It is by the Flemish artist Hans Eworth (1520-74) and based on a lost composition by Hans Holbein. The portrait normally hangs behind high table in the college dining hall from where it exudes royal power and prerogative. The second painting to be shown at the Fitzwilliam was this one: Sir Joshua Reynolds’ portrait of William Frederick, 2nd Duke of Gloucester.

The portrait shows William Frederick, George III’s nephew and future son-in-law, standing proud at the tender age of four. Reynolds, the master portraitist, gives him a stature and confidence beyond his years. How does he achieve this? By using the tools of his trade - pose, costume, facial expression and setting. The boy’s stance, left foot forward and right arm extended to hold his feathered hat and cane, is one of authority. His dusky pink suit with lace collar and cuffs looks back to royal portraits by Van Dyck. His direct stare radiates a sense of entitlement, while the low horizon of the landscape forces the viewer to look up to him. Painted in 1780, the picture shows Reynolds, the preeminent portrait painter of the time, at the height of his power. He was, by then, the first President of the Royal Academy (founded in 1768) and only the second artist to receive a knighthood. One contemporary conceded that his genius was to combine truth with fiction. So what of the subject himself? William Frederick was the only son of William Henry, 1st Duke of Gloucester, the younger brother of George III. Through his mother, Maria Walpole, the illegitimate daughter of Edward Walpole, he was the grandson of Sir Robert Walpole, the first British Prime Minister, giving him a distinguished, if slightly complicated, family tree. The young aristocrat was admitted to Trinity College in 1787, aged 11, and gained his degree three years later. He was, however, no child prodigy and was later renowned for his foolishness rather than his intellect, gaining him the nickname “Silly Billy”. Described by a contemporary as being “large and stout, but with weak, helpless legs”, his pomposity and appearance made him the butt of many satirical cartoons by the likes of James Gillray and others. None of this hindered his army career where he rose to the rank of Field Marshal in 1816 or his appointment as Chancellor of the University of Cambridge from 1811 until his death. Did Sir Joshua Reynolds recognise some of his sitter’s character when he painted this portrait or perhaps he painted what his patron wanted to see? Whatever the answer, the painting is one of the most striking and engaging in the college’s collection. Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), William Frederick, 2nd Duke of Gloucester (1776-1834), 1780, oil on canvas, 136 x 98 cm, Trinity College, Cambridge.

1 Comment

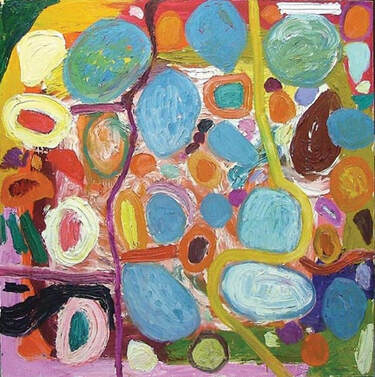

Walking into the Fellows Drawing Room at Murray Edwards College the first thing you see is a large painting hanging above the fireplace. In most other Oxbridge colleges a painting in this position would probably be a portrait of an eminent master or alumnus but not at Murray Edwards. Founded in the 1950s and formerly known as New Hall, the college prides itself on being a bastion of women’s education and also boasts one of the largest collections of contemporary women’s art in the world. It is fitting that the painting above the fireplace, a riot of pulsating colours, shapes and forms, is by the ‘grande dame’ of British abstraction Gillian Ayres RA OBE. Gillian Ayres (1930-2018) was born in London and studied at Camberwell School of Art alongside other well known British abstract artists such as Roger Hilton and Howard Hodgkin. Her early work was influenced by Jackson Pollock and American Abstract Expressionism but she went on to develop her own visual language, applying paint with thick impasto, juxtaposing forms and celebrating colour. She has been described as being “besotted by paint - what it felt like physically and what she could do with it. She used her hands, brushes, parts of cardboard boxes and brooms to arrange the vivid images that distinguished her work for more than 60 years”. The title of the New Hall painting, “Sun, Stars, Dawn” may imply a subject. Are the circular shapes a depiction of the planets? The orange and lilac a reference to the sunrise? Gillian Ayres resisted the call for such explanations: “People like to understand, and I wish they wouldn’t, I wish they’d just look. It’s visual … I don’t want this sort of understanding. There is no understanding.” The fellows of Murray Edwards College may beg to disagree as they rest from their academic labours to meet in the drawing room, which was recently refurbished with a rug and furniture designed to complement the painting. Surely the need to understand and make sense of the world is an inherent part of our human nature? The art of Gillian Ayres invites us to shake off this perceived wisdom by embracing the visual, enjoying colour for colour’s sake and revelling in the mystery of the unknown. Gillian Ayres (1930-2018), Sun, Stars, Dawn, 1996, oil on canvas, 198 x 198 cm, New Hall Art Collection, Murray Edwards College, Cambridge; the Fellows Drawing Room at Murray Edwards College.Quotes from Richard Sandomir's obituary in the New York Times, 15th April 2018 and from Gillian Ayres' interview with Jan Dally, FT Life and Arts, 2015

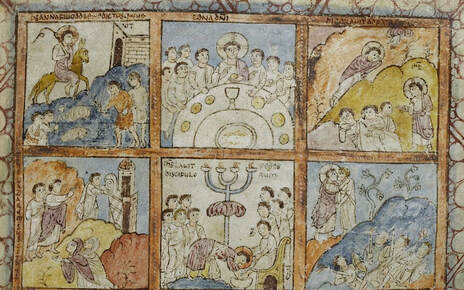

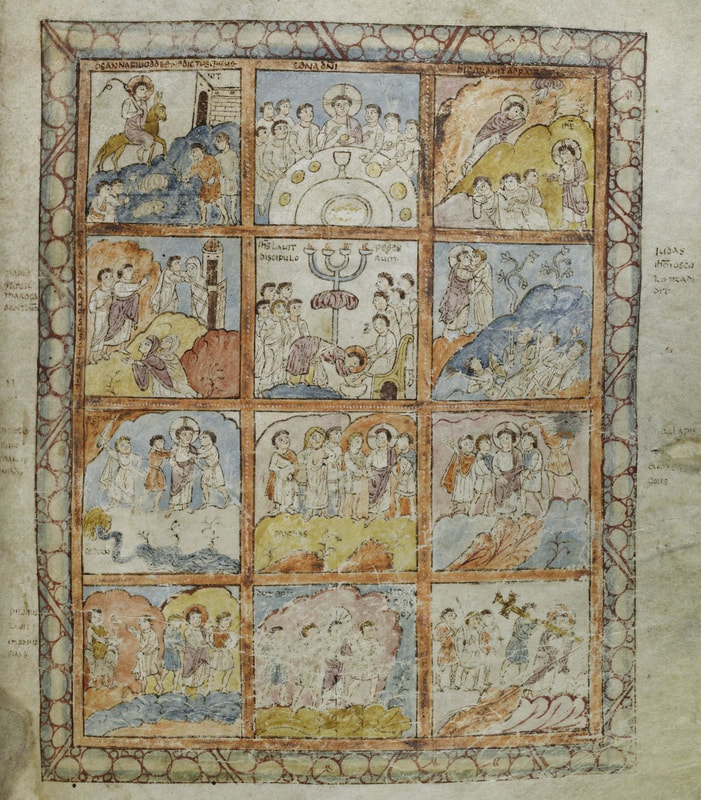

Today is Maundy Thursday, the day when Christians remember the Last Supper, the Passover meal that Jesus shared with his disciples the night before his arrest. There are many famous artistic depictions of this scene but one of my favourites is in the Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. It is also one of the oldest. This small illustration is one of twelve comic-strip style scenes from a page of the Gospels of St Augustine, the earliest surviving Gospel Book with figure illumination. The book is believed to have been brought to England by St Augustine when he was sent by Pope Gregory the Great to bring Christianity to England in 597. Unsurprisingly, some of the illuminations have been lost but two pages of images survive: the frontispiece to Luke's gospel and the illustrations from the Passion narrative. Above is a detail of six of these scenes, showing from top left the Entry into Jerusalem, the Last Supper, the Garden of Gethsemane, the Betrayal of Christ, Christ washing the feet of his disciples and the Raising of Lazarus. Why Lazarus you may ask? His story is not strictly speaking part of the Passion narrative but it is included here because John's gospel suggests it was the reason that the Jewish authorities decided to take action against Jesus. There is another incongruity. In the Last Supper scene there are eight rather than twelve disciples. They are gathered around a circular table with Christ seated in the middle. He is easily recognisable from the cruciform halo behind his head. The simple, naive style makes this image, like the others on the page, easy to read. This is important. The page was designed to be didactic, a visual explanation of the Latin text. At the table all eyes are on Jesus, as the disciples listen intently to what He is saying, although they are yet to understand its significance. He holds the bread in his hand - "this is my body given for you; do this in remembrance of me" (Luke 22:19) - it is the moment of the first Eucharist. I like to imagine St Augustine arriving in Kent in the late 6th century with this precious manuscript in his saddle bag. Then, as now, it would have been a rare and treasured object. Then, as now, it was a book that travelled. In recent years the journey has been from Cambridge to Canterbury where, since 1945, new Archbishops of Canterbury swear an oath on the book as part of their enthronement service, reflecting its deep significance in our nation's Christian heritage. As Dr Christopher de Hamel, former fellow librarian at Corpus Christi College, says: "It is very moving that a book of such a date still has the power to focus the mind spiritually". Whether or not you will be attending a 'virtual' Easter service this weekend, have a very Happy Easter. The Gospels of St Augustine of Canterbury, MS 286, in Latin, made in Italy or Gaul, 6th century, parchment, 25 x 19 cm, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, Above: detail of Folio 125r, Below: Folio 129v and 125r

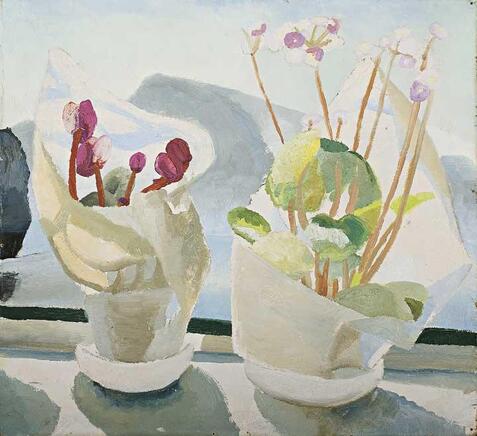

On my last visit to Kettle Yard, just three weeks ago, I learnt something new. This, in itself, is not unusual. It happens each time I visit the house as I invariably see something I missed on previous occasions. It may be a natural object juxtaposed with a painting, a cylindrical jar standing proud in the midst of potted plants or the ephemeral effect of light falling on the wooden floorboards.

This time I was looking at Winifred Nicholson's Cyclamen and Primula, painted almost 100 years ago. Born Winifred Roberts, she was already an established artist when she met and married Ben Nicholson in 1920. A few years later they became neighbours of Jim and Helen Ede in Hampstead. Jim later wrote that it was the Nicholsons who introduced him to contemporary art and that "Winifred .. taught me much about the fusing of art and daily living, and Ben that traffic in Piccadilly had the rhythm of a ballet, and a game of tennis the perfection of an old master. Life with them at once seemed lively, satisfying and special". This painting of a cyclamen and a primula sitting on a window sill seems to epitomise this fusion of art and life. What could be more everyday? Yet Winifred Nicholson gives her quotidian subjects a beauty, balance and dignity beyond the ordinary. The two plants, still in their paper wrapping, seem to salute one another. The muted overall colour scheme is broken up by the purple of the cyclamen flowers and the sharp yellows and green of the primula leaves. Light floods through the window to cast sharp shadows onto the sill. In the background are the mountains of Switzerland where Ben and Winifred bought a house in 1921 and spent their summers. What I didn't know until my last visit to Kettles Yard was that the inspiration for these paintings was a gift from Ben. Winifred later wrote "Ben had given me a pot of lilies of the valley ... in a tissue paper wrapper – this I stood on the window sill – behind was the azure blue, Mountain, Lake, Sky, all there – and the tissue paper wrapper held the secret of the universe ... after that the same theme painted itself on that window sill, in cyclamen, primula or cineraria ... I have often wished for another painting spell like that, but never had one." Jim Ede bought the painting over 30 years later in the late 1950s when it was offered to him by a Cambridge art dealer. It was covered in dirt and barely visible but after he had given it "a good scrubbing" he described it as a "delight of sunlit shadows and insubstantial substance". If you want to see the sunlit shadows at Kettles Yard you can visit the House via their live webcam http://www.kettlesyard.co.uk/kettles-yard-webcam/. Look out for William Staithe Murray's Jar (The Heron) next to Ben Nicholson's 1944 (mugs) in the top left. You'll have the whole house to yourself and as Jim wrote to an undergraduate in 1964 "Do come in as often as you like - the place is only alive when used". Cyclamen and Primula, 1923 (circa), Winifred Nicholson (1893-1981) Oil on board, 50 x 55 cm, © trustees of Winifred Nicholson. Photo credit: Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge |

AuthorAll posts written and researched by Sarah Burles, founder of Cambridge Art Tours. The 'Art Lover's Guide to Cambridge' was sent out weekly during the first Covid 19 lockdown while Cambridge museums, libraries and colleges were closed. Archives

December 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed