|

Sometimes less is more. This is certainly true of Gaudier-Brzeska’s 'Dog' which sits at the top of a small flight of steps leading from the Bechstein Room to the Bridge at Kettles Yard. The young sculptor has refined and reduced the animal’s form to its essentials - head, eyes, ears, body and legs. None of these elements are in proportion or depicted in detail and yet the dog is immediately recognisable. Henri Gaudier was born in France but moved to London in 1911 with Sophie Brzeska, a Polish writer 19 years his senior, whose name he adopted. By 1914, when this sculpture was originally carved, Gaudier-Brzeska was associated with a group of artists called the Vorticists led by Wyndham Lewis and Ezra Pound. Their aim was to create a dynamic form of modern art partly inspired by Cubism but also reflecting the machine age and the urban environment. The sharp angles of the dog’s nose and tail may have a mechanical feel but the curves of the back and ears give the sculpture a humorous realism that make it immediately appealing. The original sculpture was carved in marble but a number of bronze casts were made in the 1960s, of which this is one. Tragically, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska died aged 24 while on active service in the First World War. He left the contents of his studio to Sophie Brzeska and after her death in 1925, Jim Ede, the founder of Kettles Yard, became involved in the disposal of her estate. Unable to find interested buyers, he bought much of the collection himself and became a champion of the artist’s work, publishing a biography of Gaudier-Brzeska in 1931 entitled “Savage Messiah”. As with other artists who die young, it is pure speculation to consider what Gaudier-Brzeska would have gone on to achieve. His sculptures, drawings and paintings are at the heart of the Kettles Yard collection. Hopefully, it’s now not too long before we can be back in the House enjoying them. When you are able to visit again, make sure you don’t miss the dog on the step! Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (1891-1915) Dog, 1914, posthumous cast in bronze 1965, 15 x 35 x 8 cm; view of the Bechstein Room from the Bridge, showing 'Dog' at the top of the steps, both Kettles Yard, University of Cambridge.

0 Comments

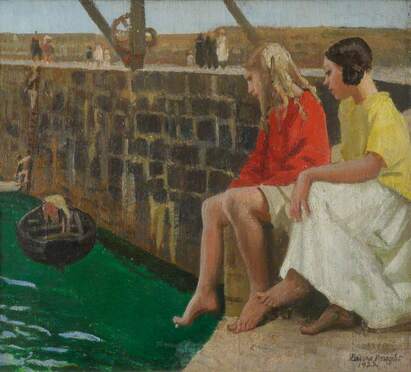

Two girls sit by a jetty together staring into the water, watching the ripples and feeling a gentle sea breeze on their faces. Their bright orange and yellow shirts stand out against the brown brickwork and complement the blue green water below. The girls appear pensive and silent. Time stands still.

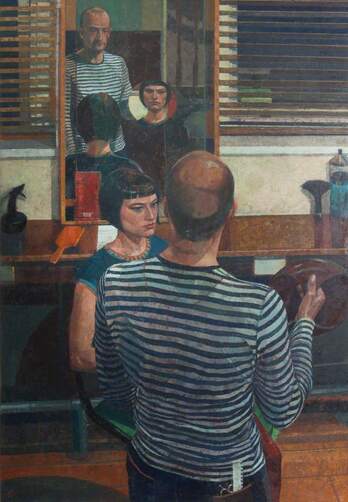

This painting is by Laura Knight, one of the leading artists of her generation, who in 1936 became the first woman to be elected a full member of the Royal Academy since its foundation in 1768. She had already won the accolade of being the first artist to be made a Dame of the British Empire. More breakthroughs followed after the war. In 1965, she was the first woman artist to have a solo retrospective at the Royal Academy and to attend the Academicians previously all male dinner. Laura Knight came from a humble background. Her mother was a single parent who taught part time at Nottingham School of Art enabling her to secure a free place for her talented 13 year old daughter. It was there that Laura met her future husband Harold Knight, one of the school’s star pupils. They married in 1903 and initially based themselves at the artists’ colony and fishing village of Staithes in Yorkshire, before moving to Cornwall in 1908. Here they played a key part in the vibrant artistic community around Newlyn and Lamorna. At the end of the First World War, the Knights moved to London, but they continued to make regular visits to Cornwall. This painting is signed and dated 1922, so it was painted during one of these later visits. The models are thought to be Mornie Birch (right) and Joy Newton, the daughters of their friends and fellow artists ‘Lamorna’ Birch and Algernon Newton. At the time the girls would have been about 18 and 16 years old respectively. Like some of her earlier Cornish paintings, Laura Knight shows young women outside, independent, unchaperoned and at ease in the landscape. What would the future hold for them? The question is one that the young women studying at Newnham College may ask themselves today. The life and work of Laura Knight should show them that anything is possible. Dame Laura Knight 1877-1970) Two Girls by a Jetty, 1922, oil on canvas, 34 x 38 cm, © reproduced with permission of the estate of Dame Laura Knight DBE, RA / Bridgeman Images, Photo credit: Newnham College, University of Cambridge “The Hairdresser” seems a particularly appropriate image to share with you this week as hair salons reopen and some of us have finally been able to get a haircut. This painting is part of the People’s Portraits Collection at Girton College which began as a millennium project, initiated by the Royal Society of Portrait Painters. The aim of the project was to provide a snapshot of Britain in the year 2000 by commissioning a series of portraits of “ordinary” people going about their daily lives. The collection includes portraits of butchers, postmistresses, motorbike couriers, lifeboatmen and many more and is now on permanent loan to Girton College. Here the portraits hang in stark contrast to those of worthy academics found on the walls of most other Cambridge colleges.

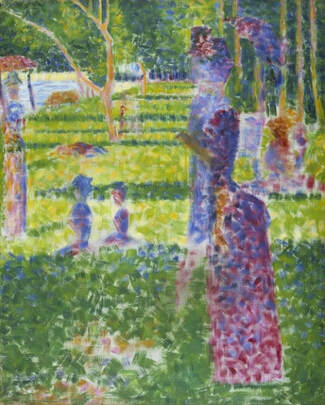

Saied Dai, the artist, was born in Iran and moved to the UK when he was six. He began his training as an architect, before going on to study painting at the Royal Academy School. He describes portraiture as ‘the most complex of the visual idioms, both structurally and psychologically, and consequently the most fascinating, as one is dealing with humanity itself or in mirror reflection, ourselves. It is also a microcosm in which one can explore almost all the problems of drawing and painting.” The painting turns on its head the traditional portrait composition in which the subject is positioned at the front of the picture plane and looks out to the viewer. Here, the subject stands with his back to us, while his client looks to one side as she views her recently cropped hair in the mirror. The reflected image of the hairdresser himself stands at the back of the painting, job done. These two figures appear in the painting a total of five different times. Saied Dai ascribes a more universal meaning to the painting: 'The subject of 'The Hairdresser' is in reality a metaphor for the Artist and the Muse. The painting depicts a scene where all activity has finally ceased, but for the contemplation of the artist and his work. A complex composition is set up involving multiple mirror images, resulting in ambiguities between the actual and its reflected equivalent.’ It is these ambiguities that encourage us to look more carefully at the painting and see that this is no “ordinary” portrait. In turn, the People’s Portrait collection as a whole shows us that there are no “ordinary” people. Each portrait in the collection reveals an individual with their own unique and often fascinating life story. Saied Dai (b 1958) The Hairdresser, 2008, oil on canvas, 120 x 74 cm, on loan from the Royal Society of Portrait Painters to Girton College, Cambridge as part of the People's Portrait Collection Image © the artist. Photo credit: Girton College, University of Cambridge The Fitzwilliam Museum is fortunate to have one of only three large-scale oil studies of Seurat’s iconic painting “A Sunday on the Island of La Grande Jatte” 1884/6 (Art Institute of Chicago). Although the painting is usually on display at the Fitzwilliam, it actually belongs to the Provost and Fellows of Kings College and is here in Cambridge thanks to the economist John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946). Keynes was a member of the Bloomsbury Group and began collecting art under the influence and encouragement of the art critic Roger Fry. When he died he left 143 works to Kings College including paintings by Cézanne, Renoir, Picasso and Braque as well as his Bloomsbury friends Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell.

The Seurat study is one of Keynes’ most significant purchases. It reveals the way Seurat prepared and planned for his finished masterpiece which caused a sensation when it was exhibited at the eighth and last Impressionist exhibition in May 1886. In the study, Seurat sketches out the forms and colour combinations for the final painting, as well as the passages of light and shade. A number of grid lines are visible under the paint layer which he used to transfer the layout onto the enormous finished canvas. The paint is applied with loose, short brushstrokes that create a patchwork of diagonal marks. In contrast, Seurat’s finished painting is much more precise. In it he perfects the technique that became known as ‘pointillism’ which involved applying small dots of unmixed pigment, often in complementary colours, to create the forms. Seurat was fascinated by colour theories which showed that the eye would then read these dots as blocks of luminous colour. The scene is a view of Parisiennes at leisure on an island in the Seine. Here we can see the two standing figures who have a prominent position in the finished painting. Their identity has been a subject of much debate. Is the woman a prostitute with her client or a well-to-do member of the bourgeoisie? The study gives us even fewer clues than the finished painting - the man and woman are faceless and enigmatic. John Maynard Keynes bought the Fitzwilliam study in the early 1920s and it certainly proved a good investment. A recent study by academics at the Judge Business School estimated that Keynes spent about £13,000 on his art collection over his lifetime and that its market value was approximately £76 million in early 2019. I’ll leave the mathematicians among you to do the sums but what money can’t buy is the thrill of seeing the artist’s hand at work in this study as he plans for what is considered to be his greatest masterpiece. Georges-Pierre Seurat (1859-1891) Study for A Sunday on the Island of La Grande Latte: Couple Walking, 1884-6, oil on canvas with squaring up in conté crayon, 81 x 65 cm, The Provost and Fellows of King's College (Keynes Collection), on loan to the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge |

AuthorAll posts written and researched by Sarah Burles, founder of Cambridge Art Tours. The 'Art Lover's Guide to Cambridge' was sent out weekly during the first Covid 19 lockdown while Cambridge museums, libraries and colleges were closed. Archives

December 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed