|

Two years ago this small sculpture was one of the key works in the Oceania exhibition at the Royal Academy. The exhibition revealed the creativity, skill and variety of art from the Pacific region, as well as the influence it had on modern European artists like Gauguin, Picasso and Matisse. This wooden carving, from the collection at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge, dates from the end of the 18th century and is a lively depiction of two figures with a dog or a pig. The sculpture is skilfully made and designed to be viewed from either side as the figures are double faced and the animal carved in the round. All three are joined together as if part of a chain or procession but the object’s function is unknown. For many years it was thought to be some kind of canoe ornament but recent research has suggested it may have been part of a gateway into a place of worship or prestigious home.

The sculpture is considered a masterpiece of oceanic art but, aside from its artistic merits, it has a fascinating story to tell. Most significantly, it was one of the artefacts collected by Captain Cook on his first voyage to the Pacific in 1769 which makes it the earliest piece of figurative sculpture to be collected by a European from any part of Oceania. It arrived in Cambridge in 1771, just three month’s after the Endeavour’s return to England. Cook had given the sculpture to his patron at the Admiralty, Lord Sandwich, who immediately presented it to Trinity College where it was kept until transferred to the museum in 1914. Recent analysis of the wood has dated the sculpture to between 1690-1730 revealing that it was a historic piece when Cook acquired it. He probably did so in Tahiti, even though the sculpture is thought to have been made in the Austral islands, some 355 miles further south. This discovery raises questions about whether it was traded, looted or gifted between the peoples of Polynesia. One side of the sculpture appears to have been broken off. What would have been there? Would the line of figures and animals have continued? Double figures like these ones are thought to represent divine power but what else might have been carved alongside them? We may never know. The sculpture retains its secrets, while the open mouthed protagonists speak across space and time of our common humanity and artistic endeavour. Sculpture of two double figures and a quadruped, c 1690-1730, ficus wood, length 51 cm, Tahiti, Society Islands, Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge

1 Comment

How many horses do you know who have a club named after them, an annual race run in their memory and were painted by George Stubbs? It’s Ascot week and here is Gimcrack, with his jockey John Pratt, standing on Newmarket Heath. The painting is thought to have been commissioned shortly after the horse’s first victory at Newmarket races on 9th April 1765.

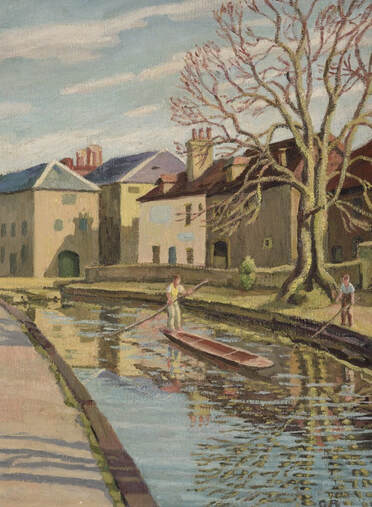

Stubbs shows horse and rider standing against the wide East Anglian sky, gazing confidently across the gallops. Behind them is the rubbing down house, where horses would be taken after a race to cool down. Stubbs, the great horse painter, shows his skill. The horse is painted with remarkable anatomical accuracy, the sheen of his coat accentuating the muscles underneath, while his face is alert and full of character. Gimcrack became a racing legend, winning 28 of his 36 races. He was relatively small for a racehorse, standing at just 14 hands, but what he lacked in stature he made up for in bravery and determination. Together with his winning record, this endeared him to the racing public. Lady Sarah Bunbury, daughter of the Duke of Richmond, was one of his many admirers, describing him as “the sweetest little horse .. that ever was”. While Gimcrack was the most successful racehorse of his day, John Pratt was the most successful jockey. Pratt is shown wearing a red jacket and black cap, the colours of Gimcrack’s owner at the time, William Wildman, the Smithfield meat salesman who commissioned the painting. Today we are used to seeing jockeys wearing coloured silks, but they had only just been introduced when Gimcrack was painted. Racing, which had been the preserve of the aristocracy, became more democratised and professional in the eighteenth century. As more horses took part in each race, it was important to be able to differentiate between runners and riders as they came thundering past. Wildman was one of Stubb’s most regular patrons. After his death in 1787 this painting was sold at auction, together with sixteen other works by Stubbs from Wildman's collection. Having changed hands several times, the painting came up for sale in 1982. To prevent it being sold abroad, the Fitzwilliam Museum launched a public appeal to buy it, receiving support from their Majesties the Queen and Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, together with other funders. To boost the appeal, the museum’s director, Professor Michael Jaffé, went to Newmarket races where he stood at the turnstiles shaking a bucket to encourage race goers to contribute to the purchase. His efforts paid off. The painting now hangs in the Fitzwilliam, just a few miles from Newmarket, immortalising horse, rider, patron and artist. Perhaps another victory for Gimcrack? George Stubbs (1724-1806) Gimcrack with John Pratt up on Newmarket Heath, 1765, oil on canvas, 100 x 127 cm, Fitzwilliam Museum A punter navigates his way quietly along the still waters of the River Cam in this atmospheric painting by Gwen Raverat. Although the bare branches of the tree suggest that it was painted in early spring rather than summer, the scene evokes memories of lazy student days and the May week celebrations which would have been taking place in Cambridge this week. There is a stillness in the air as the sunlight falls on the buildings and creates sharp reflections in the water, interrupted by gentle ripples. The composition and colours are as beautifully balanced as the punter himself.

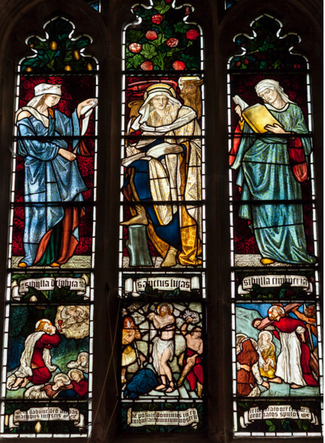

Like punting, Gwen Raverat is something of a Cambridge institution. A painter, illustrator, print-maker and writer, she was born into an eminent family. Her grandfather was Charles Darwin, the famous biologist, and her father Sir George Darwin, a fellow of Trinity College and Professor of Astronomy at Cambridge University. Her memoir, Period Piece: A Cambridge Childhood, published in 1952, describes her early life in an Edwardian academic family with humour and affection, the text interspersed with her lively illustrations. In 1908 Gwen Darwin left Cambridge to study at the Slade School of Art in London alongside artists such as Stanley Spencer, Dora Carrington and David Bomberg. She embraced the bohemian life, becoming an accomplished artist and pioneer of modern wood engraving. It was at the Slade that Gwen also met the French artist Jacques Raverat and they were married in 1911. Their circle of friends included the intellectual group known as the “Neo-Pagans” centred around Rupert Brooke, as well as members of the Bloomsbury Group such as Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, Vanessa Bell and Lytton Strachey. After the war, the Raverats spent most of their time in France, but sadly Jacques was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis and died in 1925. Now a young widow with two small children, Gwen moved back to Cambridge and, with great determination, made a successful career for herself as an art critic, book illustrator, wood engraver and painter. Examples of Gwen Raverat’s work can be found in several Cambridge collections, including the Fitzwilliam Museum and the New Hall Art Collection. This painting can be found at Darwin College, which was founded in 1964 and named after Gwen’s family. At the college's centre is Newnham Grange, the house where she grew up and returned to in the last years of her life. Sadly, this year’s May Ball at Darwin College has been cancelled but I am delighted to see that from today you can once again hire a punt on the River Cam. Gwen John (1885-1957) Cambridge Upper River, 1955, oil on canvas, 39 x 29 cm © estate of Gwen Raverat. All rights reserved, DACS 2020. Photo credit: Darwin College, University of Cambridge This striking image is a detail of a stained glass window designed by Edward Burne-Jones for the chapel of Jesus College. St Luke is easily identifiable by the winged ox, his traditional symbol, standing behind him. His long, elegant hands hold his gospel book and a quill pen. The detail is from the central panel of a window in the South Transept which is shown in full below. St Luke is flanked, on either side, by two elegant sibyls and underneath are scenes from the Passion of Christ, designed by Ford Madox Brown. Burne-Jones, like the earlier Pre-Raphaelite artists and his lifelong friend William Morris, looked back to the medieval world and the Italian Renaissance for inspiration. Burne Jones has visited Rome the year before he created the figure of St Luke. While there, he spent a day lying on his back in the Sistine Chapel looking at Michelangelo’s painted ceiling through his opera glasses. Michelangelo’s influence is clearly seen in the sculptural folds of cloth and St. Luke's strong, androgynous facial features. Edward Burne-Jones played a leading role in the revival of the stained glass tradition in Britain during the second half of the nineteenth century and his designs are found in churches all over the country. Having met William Morris at Oxford, he was one of the founding partners and the leading stained glass designer of Morris’s decorative arts firm, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Co, which was later to become Morris & Co. The eleven windows he designed for Jesus College Chapel are considered very fine examples of his work and some of the designs were reused in other churches. The commission for the Jesus College stained glass windows came through the architect George Bodley, who was called in to do repairs to the chapel in 1864. Bodley initially employed Morris to decorate the chapel's ceiling. Morris created the designs but then outsourced most of the decorative painting to the Cambridge firm of FR Leach*. At the time, this caused some consternation to the College Dean, Edmund Henry Morgan, who wrote to Bodley saying that: “Some astonishment was felt at the employment of a Cambridge workman in the execution of a work that was entrusted to Mr Morris, on the very favourable recommendation given by you”. Bodley was quick to reassure his client, replying: “I would say that Morris finds Leach a very capable and able executant …..he is doing it quite as well as Morris’s own men would”. This may have been one of the reasons that it took Bodley a little while to persuade the college to commission the stained glass windows from Morris’s firm a few years later. Luckily for Cambridge, Bodley had his way and the chapel's sumptuous windows and beautifully decorated ceiling can still be enjoyed to this day. Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) Detail of "St Luke", 1872 and full window with above: Delphic Sibyl, St Luke, Cimmerian Sibyl by Burne-Jones and below: Agony in the Garden, The Flagellation, Christ bearing the Cross by Ford Madox-Brown, stained glass window in South Transept, Jesus College Chapel

|

AuthorAll posts written and researched by Sarah Burles, founder of Cambridge Art Tours. The 'Art Lover's Guide to Cambridge' was sent out weekly during the first Covid 19 lockdown while Cambridge museums, libraries and colleges were closed. Archives

December 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed