|

Private gardens are bursting into colour and with the National Trust and RHS preparing to reopen some of their gardens next week, it is time to turn our art lovers’ eyes to flowers. What better way to do this than to return to the Fitzwilliam Museum which boasts one of the most important collections of flower paintings and drawings anywhere in the world.

Here we see the beautiful Paeonia suffruticosa by the French artist Pierre Joseph Redouté (1759-1840), one of the finest botanical draughtsman of his age. Born in Belgian into a family of artists, Redouté moved to Paris in his early 20s where he learnt the art of flower painting. He became known for his botanical accuracy as well as his balanced compositions and subtle variations of tone, all of which can be seen in this drawing. Look at the lush pink petals of the flower, the perfectly gradated green leaves and the placing of the flower on the page. It is little wonder that he has been called ‘the Raphael of flowers’. Redouté not only possessed extraordinary artistic skill, but he must also have had great powers of tact and diplomacy as he had the distinction of working for both Marie-Antoinette, as Draughtsman and Painter to the Queen’s Cabinet, and for the Empress Joséphine, first wife of Napoleon Bonaparte, as her official artist. The latter commissioned Redouté to paint the flowers grown at her chateau at Malmaison where she had an extensive collection of roses, lilies and rare plants including this Paeonia suffruticosa. The watercolour is from an album of 72 works by Redouté bequeathed to the Fitzwilliam in 1973 by Henry Rogers Broughton, 2nd Lord Fairhaven, whose family once owned Anglesey Abbey. The museum director at the time described Lord Fairhaven’s gift as an act of “breathtaking generosity”. Having already given 37 valuable flower paintings to the museum in 1966, on his death seven years later Lord Fairhaven left the museum another 82 oil paintings, 38 albums and about 900 drawings of flowers on paper and vellum. It was a legacy that transformed the museum’s collection and which will last long after the summer blooms are over. Pierre-Joseph Redouté (1759-1840) "Paeonia Suffruticosa", 1812, watercolour with body colour over traces of graphite on vellum, 46 x 34 cm, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

1 Comment

This small illumination is from a manuscript made in England in the late 13th and early 14th century and is found in the Old Library, St John’s College, Cambridge. At first glance it’s quite easy to miss the narrative. A woman stands in the centre surrounded by a group of men wearing brightly coloured robes. Her hands are held together in prayer, while others gesture in surprise and amazement. What are they all doing? The answer is at the top of the image where we can just see two feet and the bottom of a blue robe disappearing into a cloud.

It is, of course, the Biblical story of the Ascension and the two feet belong to the risen Christ.The original narrative is told at the beginning of the Book of Acts and the illuminator seems to have followed the biblical text closely: “After he said this, he was taken up before their very eyes, and a cloud hid him from their sight” (Acts 1:9). By showing only his feet, the artist captures the exact moment when Christ vanishes from the earthly realm into the presence of God. This particular iconography is found in other medieval depictions of the scene and is rather aptly referred to as the ‘Disappearing Christ’. Like many medieval manuscripts, the colours of this illumination are vibrant and well preserved. The figures stand gracefully in their flowing garments, their feet almost floating above the ground, echoing the feet of the ascending Christ. The cloud, into which he disappears, is an abstract pattern of white, orange and green. Colours held meaning in the medieval world and the green may be used here as a symbol of resurrection and new life, rather than as a reflection of a physical reality. Ascension Day, celebrated yesterday in the Western Church, has its own particular tradition at St John’s. Every year, the college choir climb up to the roof of the 163ft chapel tower and sing an Ascension carol. It all started in 1902 after a discussion between the college’s director of music, Cyril Rootham and one of the fellows, Sir Joseph Larmor. Sir Joseph insisted that a choir singing from the top of the tower would not be heard by those standing on the ground below and Cyril was keen to prove him wrong. Without telling anyone, on Ascension Day, the choir climbed the tower and as the clock struck noon, they sang an Ascension Day motet. To Cyril’s great delight, Sir Joseph opened his window in the courtyard below to hear where the music was coming from! Sadly, the choir were not able to sing from the tower this year, but we are still able to enjoy the treasures of the college’s extensive manuscript collection and look forward to hearing the choir sing on Ascension Day in 2021 - a date for the diary. Above: Canticles, Hymns and Passion of Christ, manuscript MS K. 21 folio 61v, parchment, full page size 32 x 23 cm, illustrated image approximately 10 x 8 cm, Old Library, St John's College, Cambridge. You will find a great many half length male portraits like this one on the walls of Cambridge colleges. Here we have the clergyman Benjamin Whichcote (1609-1683), a fellow of Emmanuel College, who became Provost of Kings College, Vice-Chancellor of the University and leader of a group of religious thinkers called the Cambridge Platonists. He lived through turbulent times, navigating his way through the political and religious upheavals of the English Civil War, the Interregnum and the Restoration. However what is unusual about this portrait is not the sitter but the artist. It was painted by Mary Beale (1633-1699), Britain’s first professional woman painter.

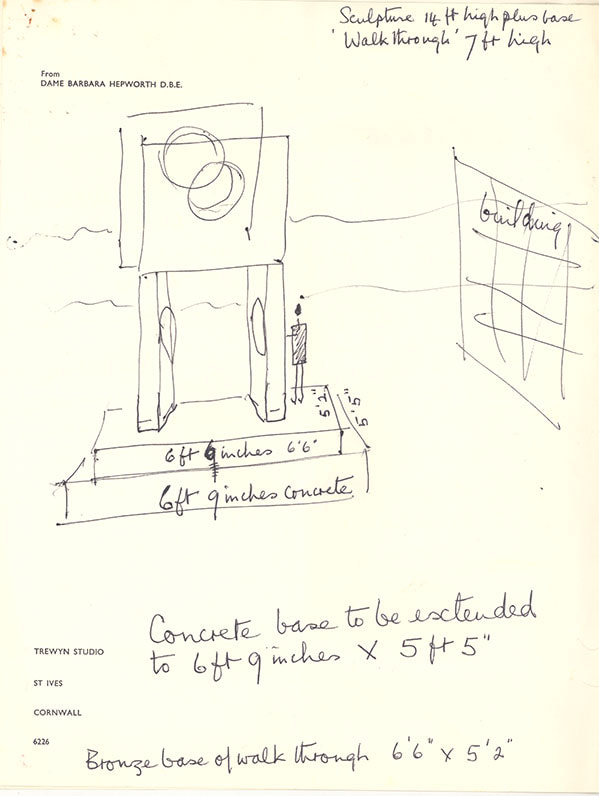

We could claim Mary Beale as a local girl. She was born about 9 miles east of Newmarket in Barrow, Suffolk, where her father was a clergyman and an amateur artist. Aged 18 she married Charles Beale, a miniaturist and artist’s colourman (a person who supplied and prepared artists’ paints) who encouraged her talent. Theirs seems to have been a harmonious, affirming and surprisingly modern relationship. In 1667, Mary wrote a “Discourse on Friendship” which argued for the equality of husband and wife in marriage, a radical concept for the time. A decade later Charles abandoned his personal ambitions in order to devote himself to organising and supporting the career of “My Dearest Heart”. By the time she painted this portrait of Whichcote in 1682, Mary Beale was one of the most celebrated portraitists in London with a busy studio on Pall Mall and a clientele that included aristocrats, leading intellectuals and clergymen. The studio was a family affair. Charles ran the business, keeping notebooks that recorded sitters, payments, pigments and materials.Their two sons, Bartholomew and Charles, helped to paint backgrounds and drapery. Mary Beale doesn’t flatter her sitter, stating once that "flattery & dissimulation... is a kind of mock friendship". Whichcote is painted with a long nose, bumpy chin and watchful eyes. From his collar hang two preaching bands which identify him as a member of the clergy. The trompe-l’oeil oval frame was a common device in seventeenth century portraiture which Mary may have learnt from her mentor Sir Peter Lely, court painter to Charles II. There has been renewed interest Mary Beale’s work in recent years with several exhibitions and a biography but she was not the only woman artist to be working in Restoration London. Records show that there were over a hundred women who were members of the Company of Painter Stainers but Mary Beale was certainly the most prolific and thanks to her husband’s meticulous notebooks, her work is well documented. Almost three hundred years before women were admitted to Emmanuel College as students, her portraits in the college’s Long Gallery blaze a trail that other women would follow. Mary Beale (1633-1699) Portrait of Benjamin Whichcote (1609-1683), 1682, oil on canvas, 73 x 61 cm, Long Gallery, Emmanuel College, Cambridge. An Art Lover's Guide to Cambridge - Dame Barbara Hepworth, Four-Square (Walk Through), 19665/8/2020 As we prepare to celebrate the 75th anniversary of VE Day, it seems appropriate to look at an iconic sculpture at Churchill College. Barbara Hepworth’s Four-Square (Walk Through) dominates the landscape beyond the college’s main concourse and is a focus for the college community, as well as a number of student pranks! Churchill College on Madingley Road was founded in 1960 as a memorial to Britain’s great wartime leader, in part inspired by a post war visit that Sir Winston Churchill made to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1949. Churchill’s vision was for a similar institute in Britain, dedicated primarily to science and technology. In a speech made on the site of the new college ten years later, he reflected on Britain’s global position: “Since we have neither the massive population, nor the raw materials, nor yet adequate agricultural land to enable us to make our way in the world with ease, we must depend for survival on our brains”. (1) The modern, Brutalist design of the new college was complemented then, as it is now, by contemporary sculpture. Barbara Hepworth, Britain’s leading sculptor and a friend of a college fellow, agreed to lend her work Squares with two circles, 1963. When it was subsequently sold to a private collector and removed, the students created their own 'Hepworth' on the plinth of the missing sculpture. The ongoing building work meant that there were plenty of bricks around - see below. The story goes that Hepworth was delighted with the students' tribute and promptly offered to provide the college with another sculpture: "I have just had cast a new work which I feel would be even better for your wonderful site. You can walk through it. It has no front and no back! Walking through is lovely as one can lean out through the lower circles & survey the landscape, or look up to the high circles & see the clouds, the sun, moon & stars.” (2) Four-Square (Walk Through) is one of Hepworth’s most monumental sculptures standing over 4 metres tall. Before she started working in bronze in the 1950s, the scale of her work had been limited by the physicality of carving in stone or wood. Bronze allowed her to create large scale works which coincided with prestigious international commissions and increased demand for public art. In Four-Square (Walk Through), she invites us to question how and what we see - "You can't look at sculpture if you don't move, experience it from all vantage-points, see how the light enters it and changes the emphasis" (3). Are the squares really square? Where do the circular voids lead the eye? How do these shapes speak to the architectural forms around them? By engaging and interacting with this huge sculpture, walking around it and through it, we are encouraged to see the world in different ways, to explore different viewpoints and to reflect on different perspectives. It is a lesson in looking and thinking as relevant today as in the 1960s. Above: Four-Square (Walk Through), Dame Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975), bronze (2/3), 429 x 199 x 229cm, Churchill College, Cambridge below: the undergraduates' tribute to Barbara Hepworth's original work, 1967 and sketch enclosed in BH letter to Kenneth McQuillen. Notes (1) Sir Winston Churchill speech, 1959 Churchill College archive CHUR5/62D/571 (2) Letter from Dame Barbara Hepworth to Dr Kenneth McQuillen, 8th October 1967. College archives, CCPP 1/10/5. (3) Barbara Hepworth quoted by Edwin Mullins, 'Scale and Monumentality: Notes and Conversations on the Recent Work of Barbara Hepworth', Sculpture International, no.4, 1967

When is a home a work of art? In Cambridge we are fortunate to have at least two examples of houses which fit that description: Kettles Yard, “a masterpiece of curatorship”, and the David Parr House, an unprepossessing terraced cottage with an extraordinary interior. The front room of the latter is shown above. David Parr (1854-1927) liked to call this the Drawing Room, perhaps a rather grand title for a room no more than a few metres wide. He was nothing if not house proud, but he had every right to be. Born into a working class family, David Parr had an inauspicious start. His mother died when he was six and his father was a ne’er do well, charged at times with theft and child cruelty. David's break came when, at the age of 17, he was taken on as an apprentice to FR Leach, a Cambridge firm of artisan decorators working with the leading designers of the day, including Charles Kempe, George Bodley and William Morris. Parr went on to become one of Leach’s best craftsmen, working on commissions from Scotland to the Isle of Wight including St James’ Palace and, closer to home, All Saints’ Church, Cambridge. By 1886 he had enough financial security to buy his own home and for the next forty years he set about transforming his small house into his own personal palace with hand painted wall decorations and many other embellishments. David Parr seems to have taken on board William Morris’s famous maxim: “Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.” Every detail of the design, each swirling leaf and abundant flower reveal the skill and dexterity of the painter’s hand and his desire to create beauty in his modest family home. While the rich could employ William Morris to redesign their houses, David Parr was talented and determined enough to do it himself. It is an astonishing achievement. What is equally astonishing is that his artistry was preserved almost intact by his granddaughter, Elsie Palmer, who lived in the house for over 80 years after her grandfather died. In a final piece of serendipity, the house was then able to be bought and conserved by the David Parr House Trust. As we admire David Parr’s Drawing Room decoration, the words of the popular Victorian verse that he inscribed on the upper text scroll seem particularly apt for today - ‘Swiftly see each moment flies, see and learn be timely wise …. seize the moments as they fly, know to live and learn to die.’ David Parr certainly ‘seized the moments’ to create a unique work of art that was his home. Above: front room of the David Parr House showing his hand painted wall decorations, family photos and Elsie's sofa, 186 Gwydir Street, Cambridge; below: detail of the text scroll on the wall decoration © David Parr House.

|

AuthorAll posts written and researched by Sarah Burles, founder of Cambridge Art Tours. The 'Art Lover's Guide to Cambridge' was sent out weekly during the first Covid 19 lockdown while Cambridge museums, libraries and colleges were closed. Archives

December 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed