|

This small illumination is from a manuscript made in England in the late 13th and early 14th century and is found in the Old Library, St John’s College, Cambridge. At first glance it’s quite easy to miss the narrative. A woman stands in the centre surrounded by a group of men wearing brightly coloured robes. Her hands are held together in prayer, while others gesture in surprise and amazement. What are they all doing? The answer is at the top of the image where we can just see two feet and the bottom of a blue robe disappearing into a cloud.

It is, of course, the Biblical story of the Ascension and the two feet belong to the risen Christ.The original narrative is told at the beginning of the Book of Acts and the illuminator seems to have followed the biblical text closely: “After he said this, he was taken up before their very eyes, and a cloud hid him from their sight” (Acts 1:9). By showing only his feet, the artist captures the exact moment when Christ vanishes from the earthly realm into the presence of God. This particular iconography is found in other medieval depictions of the scene and is rather aptly referred to as the ‘Disappearing Christ’. Like many medieval manuscripts, the colours of this illumination are vibrant and well preserved. The figures stand gracefully in their flowing garments, their feet almost floating above the ground, echoing the feet of the ascending Christ. The cloud, into which he disappears, is an abstract pattern of white, orange and green. Colours held meaning in the medieval world and the green may be used here as a symbol of resurrection and new life, rather than as a reflection of a physical reality. Ascension Day, celebrated yesterday in the Western Church, has its own particular tradition at St John’s. Every year, the college choir climb up to the roof of the 163ft chapel tower and sing an Ascension carol. It all started in 1902 after a discussion between the college’s director of music, Cyril Rootham and one of the fellows, Sir Joseph Larmor. Sir Joseph insisted that a choir singing from the top of the tower would not be heard by those standing on the ground below and Cyril was keen to prove him wrong. Without telling anyone, on Ascension Day, the choir climbed the tower and as the clock struck noon, they sang an Ascension Day motet. To Cyril’s great delight, Sir Joseph opened his window in the courtyard below to hear where the music was coming from! Sadly, the choir were not able to sing from the tower this year, but we are still able to enjoy the treasures of the college’s extensive manuscript collection and look forward to hearing the choir sing on Ascension Day in 2021 - a date for the diary. Above: Canticles, Hymns and Passion of Christ, manuscript MS K. 21 folio 61v, parchment, full page size 32 x 23 cm, illustrated image approximately 10 x 8 cm, Old Library, St John's College, Cambridge.

1 Comment

You will find a great many half length male portraits like this one on the walls of Cambridge colleges. Here we have the clergyman Benjamin Whichcote (1609-1683), a fellow of Emmanuel College, who became Provost of Kings College, Vice-Chancellor of the University and leader of a group of religious thinkers called the Cambridge Platonists. He lived through turbulent times, navigating his way through the political and religious upheavals of the English Civil War, the Interregnum and the Restoration. However what is unusual about this portrait is not the sitter but the artist. It was painted by Mary Beale (1633-1699), Britain’s first professional woman painter.

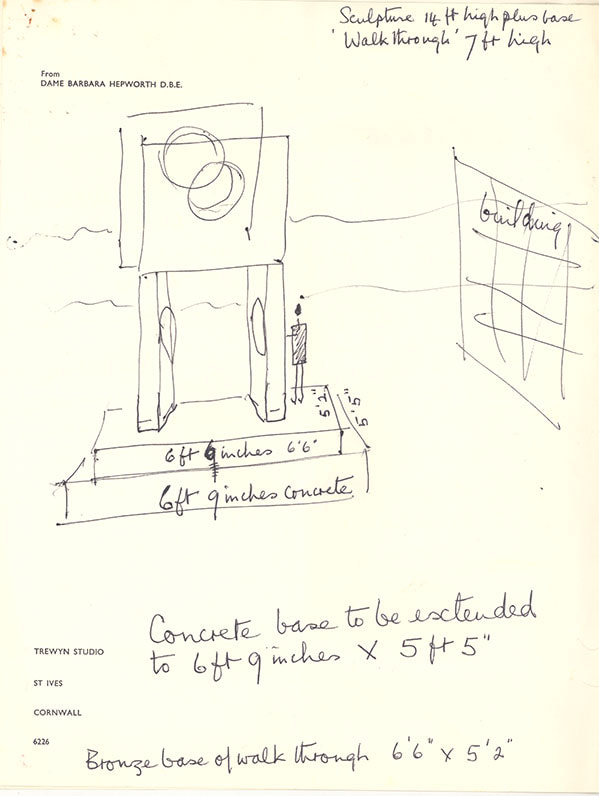

We could claim Mary Beale as a local girl. She was born about 9 miles east of Newmarket in Barrow, Suffolk, where her father was a clergyman and an amateur artist. Aged 18 she married Charles Beale, a miniaturist and artist’s colourman (a person who supplied and prepared artists’ paints) who encouraged her talent. Theirs seems to have been a harmonious, affirming and surprisingly modern relationship. In 1667, Mary wrote a “Discourse on Friendship” which argued for the equality of husband and wife in marriage, a radical concept for the time. A decade later Charles abandoned his personal ambitions in order to devote himself to organising and supporting the career of “My Dearest Heart”. By the time she painted this portrait of Whichcote in 1682, Mary Beale was one of the most celebrated portraitists in London with a busy studio on Pall Mall and a clientele that included aristocrats, leading intellectuals and clergymen. The studio was a family affair. Charles ran the business, keeping notebooks that recorded sitters, payments, pigments and materials.Their two sons, Bartholomew and Charles, helped to paint backgrounds and drapery. Mary Beale doesn’t flatter her sitter, stating once that "flattery & dissimulation... is a kind of mock friendship". Whichcote is painted with a long nose, bumpy chin and watchful eyes. From his collar hang two preaching bands which identify him as a member of the clergy. The trompe-l’oeil oval frame was a common device in seventeenth century portraiture which Mary may have learnt from her mentor Sir Peter Lely, court painter to Charles II. There has been renewed interest Mary Beale’s work in recent years with several exhibitions and a biography but she was not the only woman artist to be working in Restoration London. Records show that there were over a hundred women who were members of the Company of Painter Stainers but Mary Beale was certainly the most prolific and thanks to her husband’s meticulous notebooks, her work is well documented. Almost three hundred years before women were admitted to Emmanuel College as students, her portraits in the college’s Long Gallery blaze a trail that other women would follow. Mary Beale (1633-1699) Portrait of Benjamin Whichcote (1609-1683), 1682, oil on canvas, 73 x 61 cm, Long Gallery, Emmanuel College, Cambridge. An Art Lover's Guide to Cambridge - Dame Barbara Hepworth, Four-Square (Walk Through), 19665/8/2020 As we prepare to celebrate the 75th anniversary of VE Day, it seems appropriate to look at an iconic sculpture at Churchill College. Barbara Hepworth’s Four-Square (Walk Through) dominates the landscape beyond the college’s main concourse and is a focus for the college community, as well as a number of student pranks! Churchill College on Madingley Road was founded in 1960 as a memorial to Britain’s great wartime leader, in part inspired by a post war visit that Sir Winston Churchill made to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1949. Churchill’s vision was for a similar institute in Britain, dedicated primarily to science and technology. In a speech made on the site of the new college ten years later, he reflected on Britain’s global position: “Since we have neither the massive population, nor the raw materials, nor yet adequate agricultural land to enable us to make our way in the world with ease, we must depend for survival on our brains”. (1) The modern, Brutalist design of the new college was complemented then, as it is now, by contemporary sculpture. Barbara Hepworth, Britain’s leading sculptor and a friend of a college fellow, agreed to lend her work Squares with two circles, 1963. When it was subsequently sold to a private collector and removed, the students created their own 'Hepworth' on the plinth of the missing sculpture. The ongoing building work meant that there were plenty of bricks around - see below. The story goes that Hepworth was delighted with the students' tribute and promptly offered to provide the college with another sculpture: "I have just had cast a new work which I feel would be even better for your wonderful site. You can walk through it. It has no front and no back! Walking through is lovely as one can lean out through the lower circles & survey the landscape, or look up to the high circles & see the clouds, the sun, moon & stars.” (2) Four-Square (Walk Through) is one of Hepworth’s most monumental sculptures standing over 4 metres tall. Before she started working in bronze in the 1950s, the scale of her work had been limited by the physicality of carving in stone or wood. Bronze allowed her to create large scale works which coincided with prestigious international commissions and increased demand for public art. In Four-Square (Walk Through), she invites us to question how and what we see - "You can't look at sculpture if you don't move, experience it from all vantage-points, see how the light enters it and changes the emphasis" (3). Are the squares really square? Where do the circular voids lead the eye? How do these shapes speak to the architectural forms around them? By engaging and interacting with this huge sculpture, walking around it and through it, we are encouraged to see the world in different ways, to explore different viewpoints and to reflect on different perspectives. It is a lesson in looking and thinking as relevant today as in the 1960s. Above: Four-Square (Walk Through), Dame Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975), bronze (2/3), 429 x 199 x 229cm, Churchill College, Cambridge below: the undergraduates' tribute to Barbara Hepworth's original work, 1967 and sketch enclosed in BH letter to Kenneth McQuillen. Notes (1) Sir Winston Churchill speech, 1959 Churchill College archive CHUR5/62D/571 (2) Letter from Dame Barbara Hepworth to Dr Kenneth McQuillen, 8th October 1967. College archives, CCPP 1/10/5. (3) Barbara Hepworth quoted by Edwin Mullins, 'Scale and Monumentality: Notes and Conversations on the Recent Work of Barbara Hepworth', Sculpture International, no.4, 1967

When is a home a work of art? In Cambridge we are fortunate to have at least two examples of houses which fit that description: Kettles Yard, “a masterpiece of curatorship”, and the David Parr House, an unprepossessing terraced cottage with an extraordinary interior. The front room of the latter is shown above. David Parr (1854-1927) liked to call this the Drawing Room, perhaps a rather grand title for a room no more than a few metres wide. He was nothing if not house proud, but he had every right to be. Born into a working class family, David Parr had an inauspicious start. His mother died when he was six and his father was a ne’er do well, charged at times with theft and child cruelty. David's break came when, at the age of 17, he was taken on as an apprentice to FR Leach, a Cambridge firm of artisan decorators working with the leading designers of the day, including Charles Kempe, George Bodley and William Morris. Parr went on to become one of Leach’s best craftsmen, working on commissions from Scotland to the Isle of Wight including St James’ Palace and, closer to home, All Saints’ Church, Cambridge. By 1886 he had enough financial security to buy his own home and for the next forty years he set about transforming his small house into his own personal palace with hand painted wall decorations and many other embellishments. David Parr seems to have taken on board William Morris’s famous maxim: “Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.” Every detail of the design, each swirling leaf and abundant flower reveal the skill and dexterity of the painter’s hand and his desire to create beauty in his modest family home. While the rich could employ William Morris to redesign their houses, David Parr was talented and determined enough to do it himself. It is an astonishing achievement. What is equally astonishing is that his artistry was preserved almost intact by his granddaughter, Elsie Palmer, who lived in the house for over 80 years after her grandfather died. In a final piece of serendipity, the house was then able to be bought and conserved by the David Parr House Trust. As we admire David Parr’s Drawing Room decoration, the words of the popular Victorian verse that he inscribed on the upper text scroll seem particularly apt for today - ‘Swiftly see each moment flies, see and learn be timely wise …. seize the moments as they fly, know to live and learn to die.’ David Parr certainly ‘seized the moments’ to create a unique work of art that was his home. Above: front room of the David Parr House showing his hand painted wall decorations, family photos and Elsie's sofa, 186 Gwydir Street, Cambridge; below: detail of the text scroll on the wall decoration © David Parr House.

A few years ago two pictures from Trinity College were put on display at the Fitzwilliam Museum. The college has a collection of about 240 paintings, most of which are portraits of past alumni, masters and fellows but these two paintings reflected the college’s royal connections. The first was a large portrait of King Henry VIII, the college’s founder and patron. It is by the Flemish artist Hans Eworth (1520-74) and based on a lost composition by Hans Holbein. The portrait normally hangs behind high table in the college dining hall from where it exudes royal power and prerogative. The second painting to be shown at the Fitzwilliam was this one: Sir Joshua Reynolds’ portrait of William Frederick, 2nd Duke of Gloucester.

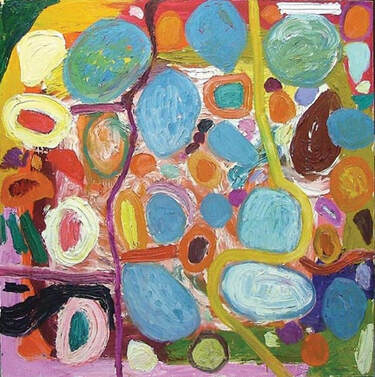

The portrait shows William Frederick, George III’s nephew and future son-in-law, standing proud at the tender age of four. Reynolds, the master portraitist, gives him a stature and confidence beyond his years. How does he achieve this? By using the tools of his trade - pose, costume, facial expression and setting. The boy’s stance, left foot forward and right arm extended to hold his feathered hat and cane, is one of authority. His dusky pink suit with lace collar and cuffs looks back to royal portraits by Van Dyck. His direct stare radiates a sense of entitlement, while the low horizon of the landscape forces the viewer to look up to him. Painted in 1780, the picture shows Reynolds, the preeminent portrait painter of the time, at the height of his power. He was, by then, the first President of the Royal Academy (founded in 1768) and only the second artist to receive a knighthood. One contemporary conceded that his genius was to combine truth with fiction. So what of the subject himself? William Frederick was the only son of William Henry, 1st Duke of Gloucester, the younger brother of George III. Through his mother, Maria Walpole, the illegitimate daughter of Edward Walpole, he was the grandson of Sir Robert Walpole, the first British Prime Minister, giving him a distinguished, if slightly complicated, family tree. The young aristocrat was admitted to Trinity College in 1787, aged 11, and gained his degree three years later. He was, however, no child prodigy and was later renowned for his foolishness rather than his intellect, gaining him the nickname “Silly Billy”. Described by a contemporary as being “large and stout, but with weak, helpless legs”, his pomposity and appearance made him the butt of many satirical cartoons by the likes of James Gillray and others. None of this hindered his army career where he rose to the rank of Field Marshal in 1816 or his appointment as Chancellor of the University of Cambridge from 1811 until his death. Did Sir Joshua Reynolds recognise some of his sitter’s character when he painted this portrait or perhaps he painted what his patron wanted to see? Whatever the answer, the painting is one of the most striking and engaging in the college’s collection. Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), William Frederick, 2nd Duke of Gloucester (1776-1834), 1780, oil on canvas, 136 x 98 cm, Trinity College, Cambridge. Walking into the Fellows Drawing Room at Murray Edwards College the first thing you see is a large painting hanging above the fireplace. In most other Oxbridge colleges a painting in this position would probably be a portrait of an eminent master or alumnus but not at Murray Edwards. Founded in the 1950s and formerly known as New Hall, the college prides itself on being a bastion of women’s education and also boasts one of the largest collections of contemporary women’s art in the world. It is fitting that the painting above the fireplace, a riot of pulsating colours, shapes and forms, is by the ‘grande dame’ of British abstraction Gillian Ayres RA OBE. Gillian Ayres (1930-2018) was born in London and studied at Camberwell School of Art alongside other well known British abstract artists such as Roger Hilton and Howard Hodgkin. Her early work was influenced by Jackson Pollock and American Abstract Expressionism but she went on to develop her own visual language, applying paint with thick impasto, juxtaposing forms and celebrating colour. She has been described as being “besotted by paint - what it felt like physically and what she could do with it. She used her hands, brushes, parts of cardboard boxes and brooms to arrange the vivid images that distinguished her work for more than 60 years”. The title of the New Hall painting, “Sun, Stars, Dawn” may imply a subject. Are the circular shapes a depiction of the planets? The orange and lilac a reference to the sunrise? Gillian Ayres resisted the call for such explanations: “People like to understand, and I wish they wouldn’t, I wish they’d just look. It’s visual … I don’t want this sort of understanding. There is no understanding.” The fellows of Murray Edwards College may beg to disagree as they rest from their academic labours to meet in the drawing room, which was recently refurbished with a rug and furniture designed to complement the painting. Surely the need to understand and make sense of the world is an inherent part of our human nature? The art of Gillian Ayres invites us to shake off this perceived wisdom by embracing the visual, enjoying colour for colour’s sake and revelling in the mystery of the unknown. Gillian Ayres (1930-2018), Sun, Stars, Dawn, 1996, oil on canvas, 198 x 198 cm, New Hall Art Collection, Murray Edwards College, Cambridge; the Fellows Drawing Room at Murray Edwards College.Quotes from Richard Sandomir's obituary in the New York Times, 15th April 2018 and from Gillian Ayres' interview with Jan Dally, FT Life and Arts, 2015

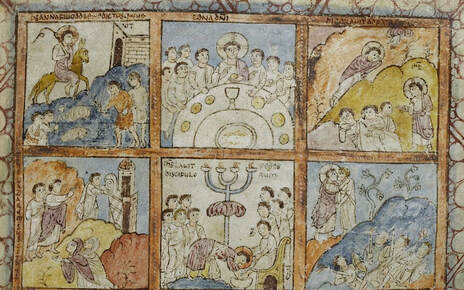

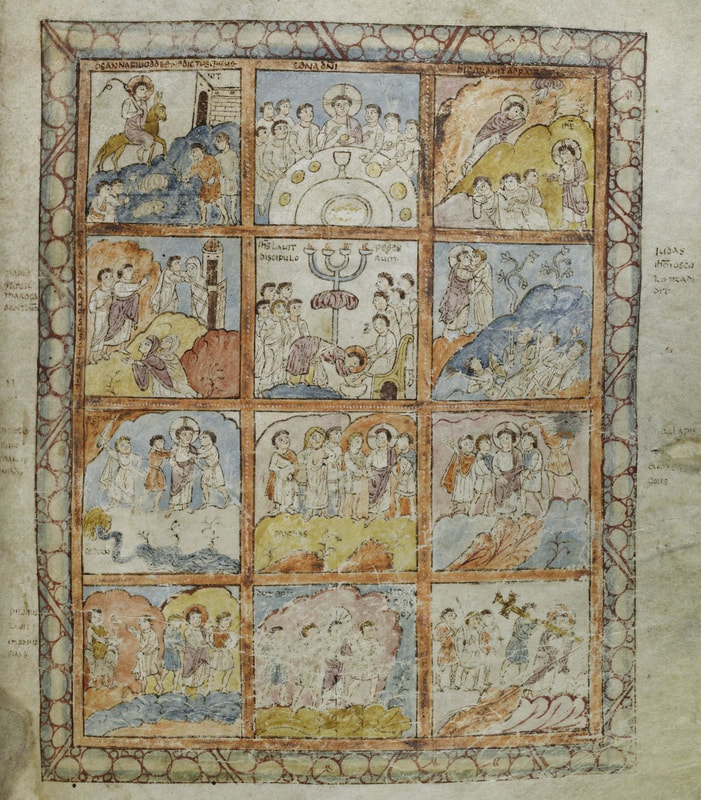

Today is Maundy Thursday, the day when Christians remember the Last Supper, the Passover meal that Jesus shared with his disciples the night before his arrest. There are many famous artistic depictions of this scene but one of my favourites is in the Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. It is also one of the oldest. This small illustration is one of twelve comic-strip style scenes from a page of the Gospels of St Augustine, the earliest surviving Gospel Book with figure illumination. The book is believed to have been brought to England by St Augustine when he was sent by Pope Gregory the Great to bring Christianity to England in 597. Unsurprisingly, some of the illuminations have been lost but two pages of images survive: the frontispiece to Luke's gospel and the illustrations from the Passion narrative. Above is a detail of six of these scenes, showing from top left the Entry into Jerusalem, the Last Supper, the Garden of Gethsemane, the Betrayal of Christ, Christ washing the feet of his disciples and the Raising of Lazarus. Why Lazarus you may ask? His story is not strictly speaking part of the Passion narrative but it is included here because John's gospel suggests it was the reason that the Jewish authorities decided to take action against Jesus. There is another incongruity. In the Last Supper scene there are eight rather than twelve disciples. They are gathered around a circular table with Christ seated in the middle. He is easily recognisable from the cruciform halo behind his head. The simple, naive style makes this image, like the others on the page, easy to read. This is important. The page was designed to be didactic, a visual explanation of the Latin text. At the table all eyes are on Jesus, as the disciples listen intently to what He is saying, although they are yet to understand its significance. He holds the bread in his hand - "this is my body given for you; do this in remembrance of me" (Luke 22:19) - it is the moment of the first Eucharist. I like to imagine St Augustine arriving in Kent in the late 6th century with this precious manuscript in his saddle bag. Then, as now, it would have been a rare and treasured object. Then, as now, it was a book that travelled. In recent years the journey has been from Cambridge to Canterbury where, since 1945, new Archbishops of Canterbury swear an oath on the book as part of their enthronement service, reflecting its deep significance in our nation's Christian heritage. As Dr Christopher de Hamel, former fellow librarian at Corpus Christi College, says: "It is very moving that a book of such a date still has the power to focus the mind spiritually". Whether or not you will be attending a 'virtual' Easter service this weekend, have a very Happy Easter. The Gospels of St Augustine of Canterbury, MS 286, in Latin, made in Italy or Gaul, 6th century, parchment, 25 x 19 cm, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, Above: detail of Folio 125r, Below: Folio 129v and 125r

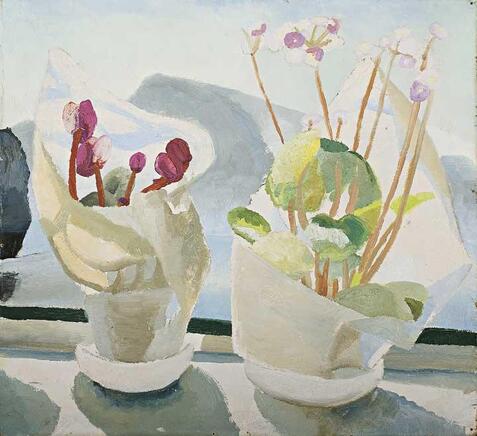

On my last visit to Kettle Yard, just three weeks ago, I learnt something new. This, in itself, is not unusual. It happens each time I visit the house as I invariably see something I missed on previous occasions. It may be a natural object juxtaposed with a painting, a cylindrical jar standing proud in the midst of potted plants or the ephemeral effect of light falling on the wooden floorboards.

This time I was looking at Winifred Nicholson's Cyclamen and Primula, painted almost 100 years ago. Born Winifred Roberts, she was already an established artist when she met and married Ben Nicholson in 1920. A few years later they became neighbours of Jim and Helen Ede in Hampstead. Jim later wrote that it was the Nicholsons who introduced him to contemporary art and that "Winifred .. taught me much about the fusing of art and daily living, and Ben that traffic in Piccadilly had the rhythm of a ballet, and a game of tennis the perfection of an old master. Life with them at once seemed lively, satisfying and special". This painting of a cyclamen and a primula sitting on a window sill seems to epitomise this fusion of art and life. What could be more everyday? Yet Winifred Nicholson gives her quotidian subjects a beauty, balance and dignity beyond the ordinary. The two plants, still in their paper wrapping, seem to salute one another. The muted overall colour scheme is broken up by the purple of the cyclamen flowers and the sharp yellows and green of the primula leaves. Light floods through the window to cast sharp shadows onto the sill. In the background are the mountains of Switzerland where Ben and Winifred bought a house in 1921 and spent their summers. What I didn't know until my last visit to Kettles Yard was that the inspiration for these paintings was a gift from Ben. Winifred later wrote "Ben had given me a pot of lilies of the valley ... in a tissue paper wrapper – this I stood on the window sill – behind was the azure blue, Mountain, Lake, Sky, all there – and the tissue paper wrapper held the secret of the universe ... after that the same theme painted itself on that window sill, in cyclamen, primula or cineraria ... I have often wished for another painting spell like that, but never had one." Jim Ede bought the painting over 30 years later in the late 1950s when it was offered to him by a Cambridge art dealer. It was covered in dirt and barely visible but after he had given it "a good scrubbing" he described it as a "delight of sunlit shadows and insubstantial substance". If you want to see the sunlit shadows at Kettles Yard you can visit the House via their live webcam http://www.kettlesyard.co.uk/kettles-yard-webcam/. Look out for William Staithe Murray's Jar (The Heron) next to Ben Nicholson's 1944 (mugs) in the top left. You'll have the whole house to yourself and as Jim wrote to an undergraduate in 1964 "Do come in as often as you like - the place is only alive when used". Cyclamen and Primula, 1923 (circa), Winifred Nicholson (1893-1981) Oil on board, 50 x 55 cm, © trustees of Winifred Nicholson. Photo credit: Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge Let's start where it all began with a painting from the Fitzwilliam Museum. "If ever you get a case of post-Christmas blues in January," I tell people when we look at it together,

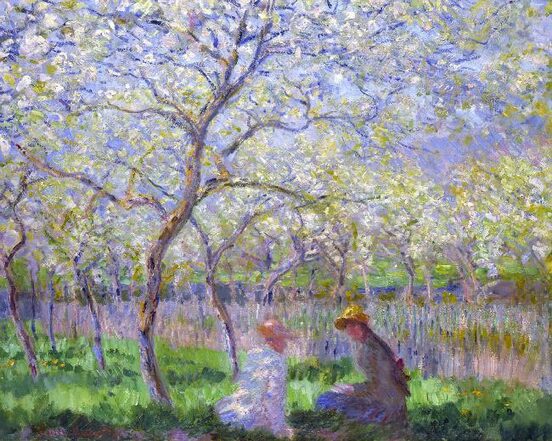

"Come and sit in front of this painting in Gallery 5 and I guarantee you will feel better". Painted in 1886 after Monet had settled in Giverny, it is a joyous reminder of nature's bounty and a glorious depiction of spring. Monet captures the moment when the orchard is just about to burst into full bloom. The sunshine through the trees casts flickering shadows on the soft grassy glades below. Seated in the foreground is Suzanne Hoschedé, the daughter of Monet's mistress and future wife Alice and his own son, Jean, whose mother, Camille, had sadly died in 1877. They sit together partly encircled in the trunk and bough of a tree, the red of Suzanne's hair ribbon contrasting with the vivid green of the grass to make it appear even brighter. Look closely at that tree trunk. It is astonishing to see how many different colours Monet used to paint it - yellow, violet, blue, pink and indigo but not a brushstroke of brown in sight. It was this use of colour, amongst other things, that appalled the critics. They accused Monet and his fellow Impressionists of "violettomania" and one commentator described the third Impressionist exhibition of 1877 as having the overall effect of a worm-eaten Roquefort cheese! Now we look at paintings like this with a sense of wonder and appreciation. A reminder in these difficult times of brighter, sunnier days ahead. Springtime, 1886, Claude Monet (1840–1926) Oil on canvas, 64.8 x 80.6 cm, Bought with the aid of the National Art Collections Fund, 1953, PD.2-1953, © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge |

AuthorAll posts written and researched by Sarah Burles, founder of Cambridge Art Tours. The 'Art Lover's Guide to Cambridge' was sent out weekly during the first Covid 19 lockdown while Cambridge museums, libraries and colleges were closed. Archives

December 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed