|

This beautiful fifteenth century panel painting hangs in the Italian gallery at the Fitzwilliam Museum and makes the perfect Christmas card. The painting is by Domenico Ghirlandaio who ran a successful workshop in Florence in the late fifteenth century and taught the young Michelangelo. All the essential elements of the Nativity are here - Mary, Joseph, the ox, the ass, the stable and an animated baby Jesus. The scene takes place in a landscape of receding hills and blue mountains. In the fields behind the stable, the angel brings the ‘glad tidings’ of Jesus’ birth to the shepherds watching their flocks. They are then seen journeying along the winding road to Bethlehem. Further in the distance are the Magi who are led to the Christ child by a golden star.

Mary is shown kneeling, her hands held in prayer as she adores her first born son. His hands reach up as if to acknowledge his earthly mother’s role in his miraculous birth. The baby lies not in a manger but on the ground. This particular iconography of the nativity became very popular in the fifteenth century and was inspired by the visions of the fourteenth century mystic and saint, Bridget of Sweden. The graceful figures and harmonious colours reflect Ghirlandaio’s assimilation of the ideas of the early Italian Renaissance while the naturalistic details of plants, animals and landscape show the influence of Flemish art on Florentine artists at this time. By combining the different elements of the story with skill and veracity, Ghirlandaio creates a timeless image of the Nativity.

1 Comment

Sometimes less is more. This is certainly true of Gaudier-Brzeska’s 'Dog' which sits at the top of a small flight of steps leading from the Bechstein Room to the Bridge at Kettles Yard. The young sculptor has refined and reduced the animal’s form to its essentials - head, eyes, ears, body and legs. None of these elements are in proportion or depicted in detail and yet the dog is immediately recognisable. Henri Gaudier was born in France but moved to London in 1911 with Sophie Brzeska, a Polish writer 19 years his senior, whose name he adopted. By 1914, when this sculpture was originally carved, Gaudier-Brzeska was associated with a group of artists called the Vorticists led by Wyndham Lewis and Ezra Pound. Their aim was to create a dynamic form of modern art partly inspired by Cubism but also reflecting the machine age and the urban environment. The sharp angles of the dog’s nose and tail may have a mechanical feel but the curves of the back and ears give the sculpture a humorous realism that make it immediately appealing. The original sculpture was carved in marble but a number of bronze casts were made in the 1960s, of which this is one. Tragically, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska died aged 24 while on active service in the First World War. He left the contents of his studio to Sophie Brzeska and after her death in 1925, Jim Ede, the founder of Kettles Yard, became involved in the disposal of her estate. Unable to find interested buyers, he bought much of the collection himself and became a champion of the artist’s work, publishing a biography of Gaudier-Brzeska in 1931 entitled “Savage Messiah”. As with other artists who die young, it is pure speculation to consider what Gaudier-Brzeska would have gone on to achieve. His sculptures, drawings and paintings are at the heart of the Kettles Yard collection. Hopefully, it’s now not too long before we can be back in the House enjoying them. When you are able to visit again, make sure you don’t miss the dog on the step! Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (1891-1915) Dog, 1914, posthumous cast in bronze 1965, 15 x 35 x 8 cm; view of the Bechstein Room from the Bridge, showing 'Dog' at the top of the steps, both Kettles Yard, University of Cambridge.

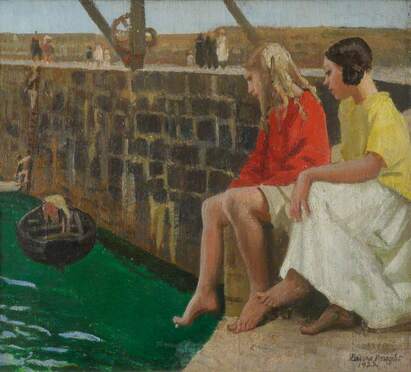

Two girls sit by a jetty together staring into the water, watching the ripples and feeling a gentle sea breeze on their faces. Their bright orange and yellow shirts stand out against the brown brickwork and complement the blue green water below. The girls appear pensive and silent. Time stands still.

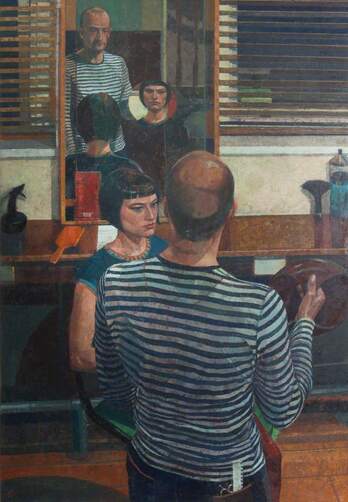

This painting is by Laura Knight, one of the leading artists of her generation, who in 1936 became the first woman to be elected a full member of the Royal Academy since its foundation in 1768. She had already won the accolade of being the first artist to be made a Dame of the British Empire. More breakthroughs followed after the war. In 1965, she was the first woman artist to have a solo retrospective at the Royal Academy and to attend the Academicians previously all male dinner. Laura Knight came from a humble background. Her mother was a single parent who taught part time at Nottingham School of Art enabling her to secure a free place for her talented 13 year old daughter. It was there that Laura met her future husband Harold Knight, one of the school’s star pupils. They married in 1903 and initially based themselves at the artists’ colony and fishing village of Staithes in Yorkshire, before moving to Cornwall in 1908. Here they played a key part in the vibrant artistic community around Newlyn and Lamorna. At the end of the First World War, the Knights moved to London, but they continued to make regular visits to Cornwall. This painting is signed and dated 1922, so it was painted during one of these later visits. The models are thought to be Mornie Birch (right) and Joy Newton, the daughters of their friends and fellow artists ‘Lamorna’ Birch and Algernon Newton. At the time the girls would have been about 18 and 16 years old respectively. Like some of her earlier Cornish paintings, Laura Knight shows young women outside, independent, unchaperoned and at ease in the landscape. What would the future hold for them? The question is one that the young women studying at Newnham College may ask themselves today. The life and work of Laura Knight should show them that anything is possible. Dame Laura Knight 1877-1970) Two Girls by a Jetty, 1922, oil on canvas, 34 x 38 cm, © reproduced with permission of the estate of Dame Laura Knight DBE, RA / Bridgeman Images, Photo credit: Newnham College, University of Cambridge “The Hairdresser” seems a particularly appropriate image to share with you this week as hair salons reopen and some of us have finally been able to get a haircut. This painting is part of the People’s Portraits Collection at Girton College which began as a millennium project, initiated by the Royal Society of Portrait Painters. The aim of the project was to provide a snapshot of Britain in the year 2000 by commissioning a series of portraits of “ordinary” people going about their daily lives. The collection includes portraits of butchers, postmistresses, motorbike couriers, lifeboatmen and many more and is now on permanent loan to Girton College. Here the portraits hang in stark contrast to those of worthy academics found on the walls of most other Cambridge colleges.

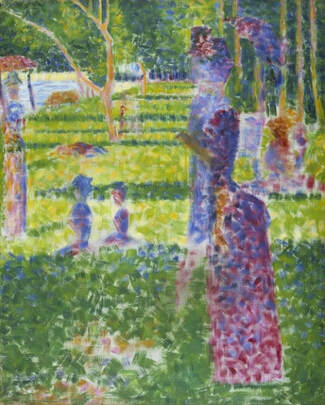

Saied Dai, the artist, was born in Iran and moved to the UK when he was six. He began his training as an architect, before going on to study painting at the Royal Academy School. He describes portraiture as ‘the most complex of the visual idioms, both structurally and psychologically, and consequently the most fascinating, as one is dealing with humanity itself or in mirror reflection, ourselves. It is also a microcosm in which one can explore almost all the problems of drawing and painting.” The painting turns on its head the traditional portrait composition in which the subject is positioned at the front of the picture plane and looks out to the viewer. Here, the subject stands with his back to us, while his client looks to one side as she views her recently cropped hair in the mirror. The reflected image of the hairdresser himself stands at the back of the painting, job done. These two figures appear in the painting a total of five different times. Saied Dai ascribes a more universal meaning to the painting: 'The subject of 'The Hairdresser' is in reality a metaphor for the Artist and the Muse. The painting depicts a scene where all activity has finally ceased, but for the contemplation of the artist and his work. A complex composition is set up involving multiple mirror images, resulting in ambiguities between the actual and its reflected equivalent.’ It is these ambiguities that encourage us to look more carefully at the painting and see that this is no “ordinary” portrait. In turn, the People’s Portrait collection as a whole shows us that there are no “ordinary” people. Each portrait in the collection reveals an individual with their own unique and often fascinating life story. Saied Dai (b 1958) The Hairdresser, 2008, oil on canvas, 120 x 74 cm, on loan from the Royal Society of Portrait Painters to Girton College, Cambridge as part of the People's Portrait Collection Image © the artist. Photo credit: Girton College, University of Cambridge The Fitzwilliam Museum is fortunate to have one of only three large-scale oil studies of Seurat’s iconic painting “A Sunday on the Island of La Grande Jatte” 1884/6 (Art Institute of Chicago). Although the painting is usually on display at the Fitzwilliam, it actually belongs to the Provost and Fellows of Kings College and is here in Cambridge thanks to the economist John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946). Keynes was a member of the Bloomsbury Group and began collecting art under the influence and encouragement of the art critic Roger Fry. When he died he left 143 works to Kings College including paintings by Cézanne, Renoir, Picasso and Braque as well as his Bloomsbury friends Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell.

The Seurat study is one of Keynes’ most significant purchases. It reveals the way Seurat prepared and planned for his finished masterpiece which caused a sensation when it was exhibited at the eighth and last Impressionist exhibition in May 1886. In the study, Seurat sketches out the forms and colour combinations for the final painting, as well as the passages of light and shade. A number of grid lines are visible under the paint layer which he used to transfer the layout onto the enormous finished canvas. The paint is applied with loose, short brushstrokes that create a patchwork of diagonal marks. In contrast, Seurat’s finished painting is much more precise. In it he perfects the technique that became known as ‘pointillism’ which involved applying small dots of unmixed pigment, often in complementary colours, to create the forms. Seurat was fascinated by colour theories which showed that the eye would then read these dots as blocks of luminous colour. The scene is a view of Parisiennes at leisure on an island in the Seine. Here we can see the two standing figures who have a prominent position in the finished painting. Their identity has been a subject of much debate. Is the woman a prostitute with her client or a well-to-do member of the bourgeoisie? The study gives us even fewer clues than the finished painting - the man and woman are faceless and enigmatic. John Maynard Keynes bought the Fitzwilliam study in the early 1920s and it certainly proved a good investment. A recent study by academics at the Judge Business School estimated that Keynes spent about £13,000 on his art collection over his lifetime and that its market value was approximately £76 million in early 2019. I’ll leave the mathematicians among you to do the sums but what money can’t buy is the thrill of seeing the artist’s hand at work in this study as he plans for what is considered to be his greatest masterpiece. Georges-Pierre Seurat (1859-1891) Study for A Sunday on the Island of La Grande Latte: Couple Walking, 1884-6, oil on canvas with squaring up in conté crayon, 81 x 65 cm, The Provost and Fellows of King's College (Keynes Collection), on loan to the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge Two years ago this small sculpture was one of the key works in the Oceania exhibition at the Royal Academy. The exhibition revealed the creativity, skill and variety of art from the Pacific region, as well as the influence it had on modern European artists like Gauguin, Picasso and Matisse. This wooden carving, from the collection at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge, dates from the end of the 18th century and is a lively depiction of two figures with a dog or a pig. The sculpture is skilfully made and designed to be viewed from either side as the figures are double faced and the animal carved in the round. All three are joined together as if part of a chain or procession but the object’s function is unknown. For many years it was thought to be some kind of canoe ornament but recent research has suggested it may have been part of a gateway into a place of worship or prestigious home.

The sculpture is considered a masterpiece of oceanic art but, aside from its artistic merits, it has a fascinating story to tell. Most significantly, it was one of the artefacts collected by Captain Cook on his first voyage to the Pacific in 1769 which makes it the earliest piece of figurative sculpture to be collected by a European from any part of Oceania. It arrived in Cambridge in 1771, just three month’s after the Endeavour’s return to England. Cook had given the sculpture to his patron at the Admiralty, Lord Sandwich, who immediately presented it to Trinity College where it was kept until transferred to the museum in 1914. Recent analysis of the wood has dated the sculpture to between 1690-1730 revealing that it was a historic piece when Cook acquired it. He probably did so in Tahiti, even though the sculpture is thought to have been made in the Austral islands, some 355 miles further south. This discovery raises questions about whether it was traded, looted or gifted between the peoples of Polynesia. One side of the sculpture appears to have been broken off. What would have been there? Would the line of figures and animals have continued? Double figures like these ones are thought to represent divine power but what else might have been carved alongside them? We may never know. The sculpture retains its secrets, while the open mouthed protagonists speak across space and time of our common humanity and artistic endeavour. Sculpture of two double figures and a quadruped, c 1690-1730, ficus wood, length 51 cm, Tahiti, Society Islands, Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge How many horses do you know who have a club named after them, an annual race run in their memory and were painted by George Stubbs? It’s Ascot week and here is Gimcrack, with his jockey John Pratt, standing on Newmarket Heath. The painting is thought to have been commissioned shortly after the horse’s first victory at Newmarket races on 9th April 1765.

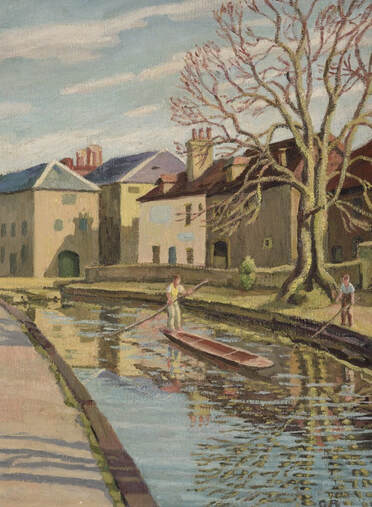

Stubbs shows horse and rider standing against the wide East Anglian sky, gazing confidently across the gallops. Behind them is the rubbing down house, where horses would be taken after a race to cool down. Stubbs, the great horse painter, shows his skill. The horse is painted with remarkable anatomical accuracy, the sheen of his coat accentuating the muscles underneath, while his face is alert and full of character. Gimcrack became a racing legend, winning 28 of his 36 races. He was relatively small for a racehorse, standing at just 14 hands, but what he lacked in stature he made up for in bravery and determination. Together with his winning record, this endeared him to the racing public. Lady Sarah Bunbury, daughter of the Duke of Richmond, was one of his many admirers, describing him as “the sweetest little horse .. that ever was”. While Gimcrack was the most successful racehorse of his day, John Pratt was the most successful jockey. Pratt is shown wearing a red jacket and black cap, the colours of Gimcrack’s owner at the time, William Wildman, the Smithfield meat salesman who commissioned the painting. Today we are used to seeing jockeys wearing coloured silks, but they had only just been introduced when Gimcrack was painted. Racing, which had been the preserve of the aristocracy, became more democratised and professional in the eighteenth century. As more horses took part in each race, it was important to be able to differentiate between runners and riders as they came thundering past. Wildman was one of Stubb’s most regular patrons. After his death in 1787 this painting was sold at auction, together with sixteen other works by Stubbs from Wildman's collection. Having changed hands several times, the painting came up for sale in 1982. To prevent it being sold abroad, the Fitzwilliam Museum launched a public appeal to buy it, receiving support from their Majesties the Queen and Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, together with other funders. To boost the appeal, the museum’s director, Professor Michael Jaffé, went to Newmarket races where he stood at the turnstiles shaking a bucket to encourage race goers to contribute to the purchase. His efforts paid off. The painting now hangs in the Fitzwilliam, just a few miles from Newmarket, immortalising horse, rider, patron and artist. Perhaps another victory for Gimcrack? George Stubbs (1724-1806) Gimcrack with John Pratt up on Newmarket Heath, 1765, oil on canvas, 100 x 127 cm, Fitzwilliam Museum A punter navigates his way quietly along the still waters of the River Cam in this atmospheric painting by Gwen Raverat. Although the bare branches of the tree suggest that it was painted in early spring rather than summer, the scene evokes memories of lazy student days and the May week celebrations which would have been taking place in Cambridge this week. There is a stillness in the air as the sunlight falls on the buildings and creates sharp reflections in the water, interrupted by gentle ripples. The composition and colours are as beautifully balanced as the punter himself.

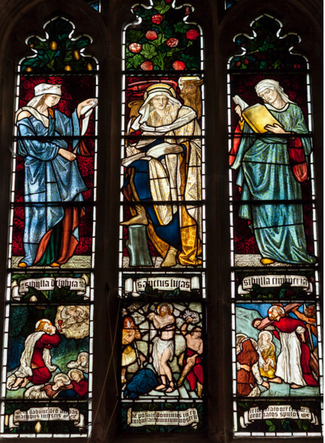

Like punting, Gwen Raverat is something of a Cambridge institution. A painter, illustrator, print-maker and writer, she was born into an eminent family. Her grandfather was Charles Darwin, the famous biologist, and her father Sir George Darwin, a fellow of Trinity College and Professor of Astronomy at Cambridge University. Her memoir, Period Piece: A Cambridge Childhood, published in 1952, describes her early life in an Edwardian academic family with humour and affection, the text interspersed with her lively illustrations. In 1908 Gwen Darwin left Cambridge to study at the Slade School of Art in London alongside artists such as Stanley Spencer, Dora Carrington and David Bomberg. She embraced the bohemian life, becoming an accomplished artist and pioneer of modern wood engraving. It was at the Slade that Gwen also met the French artist Jacques Raverat and they were married in 1911. Their circle of friends included the intellectual group known as the “Neo-Pagans” centred around Rupert Brooke, as well as members of the Bloomsbury Group such as Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, Vanessa Bell and Lytton Strachey. After the war, the Raverats spent most of their time in France, but sadly Jacques was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis and died in 1925. Now a young widow with two small children, Gwen moved back to Cambridge and, with great determination, made a successful career for herself as an art critic, book illustrator, wood engraver and painter. Examples of Gwen Raverat’s work can be found in several Cambridge collections, including the Fitzwilliam Museum and the New Hall Art Collection. This painting can be found at Darwin College, which was founded in 1964 and named after Gwen’s family. At the college's centre is Newnham Grange, the house where she grew up and returned to in the last years of her life. Sadly, this year’s May Ball at Darwin College has been cancelled but I am delighted to see that from today you can once again hire a punt on the River Cam. Gwen John (1885-1957) Cambridge Upper River, 1955, oil on canvas, 39 x 29 cm © estate of Gwen Raverat. All rights reserved, DACS 2020. Photo credit: Darwin College, University of Cambridge This striking image is a detail of a stained glass window designed by Edward Burne-Jones for the chapel of Jesus College. St Luke is easily identifiable by the winged ox, his traditional symbol, standing behind him. His long, elegant hands hold his gospel book and a quill pen. The detail is from the central panel of a window in the South Transept which is shown in full below. St Luke is flanked, on either side, by two elegant sibyls and underneath are scenes from the Passion of Christ, designed by Ford Madox Brown. Burne-Jones, like the earlier Pre-Raphaelite artists and his lifelong friend William Morris, looked back to the medieval world and the Italian Renaissance for inspiration. Burne Jones has visited Rome the year before he created the figure of St Luke. While there, he spent a day lying on his back in the Sistine Chapel looking at Michelangelo’s painted ceiling through his opera glasses. Michelangelo’s influence is clearly seen in the sculptural folds of cloth and St. Luke's strong, androgynous facial features. Edward Burne-Jones played a leading role in the revival of the stained glass tradition in Britain during the second half of the nineteenth century and his designs are found in churches all over the country. Having met William Morris at Oxford, he was one of the founding partners and the leading stained glass designer of Morris’s decorative arts firm, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Co, which was later to become Morris & Co. The eleven windows he designed for Jesus College Chapel are considered very fine examples of his work and some of the designs were reused in other churches. The commission for the Jesus College stained glass windows came through the architect George Bodley, who was called in to do repairs to the chapel in 1864. Bodley initially employed Morris to decorate the chapel's ceiling. Morris created the designs but then outsourced most of the decorative painting to the Cambridge firm of FR Leach*. At the time, this caused some consternation to the College Dean, Edmund Henry Morgan, who wrote to Bodley saying that: “Some astonishment was felt at the employment of a Cambridge workman in the execution of a work that was entrusted to Mr Morris, on the very favourable recommendation given by you”. Bodley was quick to reassure his client, replying: “I would say that Morris finds Leach a very capable and able executant …..he is doing it quite as well as Morris’s own men would”. This may have been one of the reasons that it took Bodley a little while to persuade the college to commission the stained glass windows from Morris’s firm a few years later. Luckily for Cambridge, Bodley had his way and the chapel's sumptuous windows and beautifully decorated ceiling can still be enjoyed to this day. Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) Detail of "St Luke", 1872 and full window with above: Delphic Sibyl, St Luke, Cimmerian Sibyl by Burne-Jones and below: Agony in the Garden, The Flagellation, Christ bearing the Cross by Ford Madox-Brown, stained glass window in South Transept, Jesus College Chapel

Private gardens are bursting into colour and with the National Trust and RHS preparing to reopen some of their gardens next week, it is time to turn our art lovers’ eyes to flowers. What better way to do this than to return to the Fitzwilliam Museum which boasts one of the most important collections of flower paintings and drawings anywhere in the world.

Here we see the beautiful Paeonia suffruticosa by the French artist Pierre Joseph Redouté (1759-1840), one of the finest botanical draughtsman of his age. Born in Belgian into a family of artists, Redouté moved to Paris in his early 20s where he learnt the art of flower painting. He became known for his botanical accuracy as well as his balanced compositions and subtle variations of tone, all of which can be seen in this drawing. Look at the lush pink petals of the flower, the perfectly gradated green leaves and the placing of the flower on the page. It is little wonder that he has been called ‘the Raphael of flowers’. Redouté not only possessed extraordinary artistic skill, but he must also have had great powers of tact and diplomacy as he had the distinction of working for both Marie-Antoinette, as Draughtsman and Painter to the Queen’s Cabinet, and for the Empress Joséphine, first wife of Napoleon Bonaparte, as her official artist. The latter commissioned Redouté to paint the flowers grown at her chateau at Malmaison where she had an extensive collection of roses, lilies and rare plants including this Paeonia suffruticosa. The watercolour is from an album of 72 works by Redouté bequeathed to the Fitzwilliam in 1973 by Henry Rogers Broughton, 2nd Lord Fairhaven, whose family once owned Anglesey Abbey. The museum director at the time described Lord Fairhaven’s gift as an act of “breathtaking generosity”. Having already given 37 valuable flower paintings to the museum in 1966, on his death seven years later Lord Fairhaven left the museum another 82 oil paintings, 38 albums and about 900 drawings of flowers on paper and vellum. It was a legacy that transformed the museum’s collection and which will last long after the summer blooms are over. Pierre-Joseph Redouté (1759-1840) "Paeonia Suffruticosa", 1812, watercolour with body colour over traces of graphite on vellum, 46 x 34 cm, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge |

AuthorAll posts written and researched by Sarah Burles, founder of Cambridge Art Tours. The 'Art Lover's Guide to Cambridge' was sent out weekly during the first Covid 19 lockdown while Cambridge museums, libraries and colleges were closed. Archives

December 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed